Is there a light at the end of the tunnel?

Artist Stephanie Anne Johnson thinks so, and she hopes her work can guide us.

Pam Grady, Special to The Chronicle — Thursday, August 24, 2006

Artist Stephanie Anne Johnson thinks so, and she hopes her work can guide us.

Pam Grady, Special to The Chronicle — Thursday, August 24, 2006

Stephanie Anne Johnson was about to graduate from college when she found the light. A theater major at Boston's Emerson College in the mid-1970s, she took a class in lighting design in her next-to-last semester and discovered the medium that continues to inspire her as a theatrical lighting designer and artist.

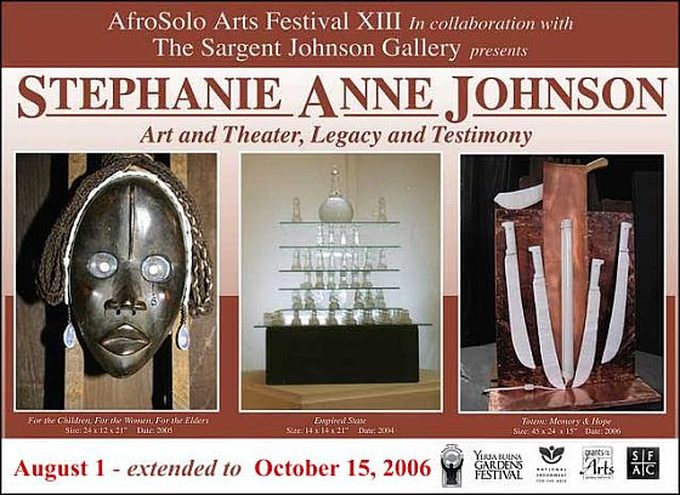

"I just loved it. I just loved it," she recalled recently as she led a visitor through a tour of her show, "Stephanie Anne Johnson: Art and Theater, Legacy and Testimony" at San Francisco's Sargent Johnson Gallery. "When I graduated, the first jobs I had were jobs doing lighting design. I became fascinated with it and just kept working with it."

A visit to the gallery confirms the artist's relationship with light. Individual pieces include totems, perspective boxes, sculpture in a variety of media, and even a small model theater where examples of nearly three decades of Johnson's lighting designs play in a continuous loop. Dominating one wall is the mixed media "The Raft of the Katrina" that uses multiple materials to simultaneously pay homage to the hurricane's victims and comment on the government's and media's response to the unfolding tragedy.

Several of the pieces employ slide projections. In all of them, Johnson integrates light in one form or another, illuminating not just the art, but also Johnson's perspective on the world.

"I just loved it. I just loved it," she recalled recently as she led a visitor through a tour of her show, "Stephanie Anne Johnson: Art and Theater, Legacy and Testimony" at San Francisco's Sargent Johnson Gallery. "When I graduated, the first jobs I had were jobs doing lighting design. I became fascinated with it and just kept working with it."

A visit to the gallery confirms the artist's relationship with light. Individual pieces include totems, perspective boxes, sculpture in a variety of media, and even a small model theater where examples of nearly three decades of Johnson's lighting designs play in a continuous loop. Dominating one wall is the mixed media "The Raft of the Katrina" that uses multiple materials to simultaneously pay homage to the hurricane's victims and comment on the government's and media's response to the unfolding tragedy.

Several of the pieces employ slide projections. In all of them, Johnson integrates light in one form or another, illuminating not just the art, but also Johnson's perspective on the world.

"My personal philosophy is that I'm doing the work of the ancestors, that I'm here to bring forth a message to help make the world better through my art, through my work, how I conduct my life, how I conduct myself. So I'm not just here for myself, but I'm continuing a legacy, an ancestral legacy, a heritage, and then supporting and maintaining that," Johnson says.

Art is an outgrowth of her work in the theater. She had been a lighting designer for nearly two decades when she began doing slide projections of her designs. That led to learning about installation art, and from there, Johnson moved to mixed media. Most recently, she began working in stone, represented in the show by "The Gift," a sculpture in Sierra gold alabaster.

Johnson's commitment to community and to using her art for the betterment of the world is an inheritance from her parents. Her mother is a retired teacher and social worker whose work with the American Negro Theater inspired her daughter to follow in her footsteps. Her late father was a child psychologist in the Bronx, whose life was irreparably damaged by the racism of the 1940s and '50s, and who worked to combat the racism that then pervaded the schools.

"That's the kind of legacy of paying attention, of giving back, that, you know, I'm standing on his shoulders. And my mother's shoulders," Johnson says.

In the show, she pays homage to that legacy with "Perspective Box #2," combining Plexiglas, light, photographs and holographic images. "That was not an easy piece to make," Johnson says of the work that is dominated by boyhood photographs of her father. "Really, what it's about is the kind of innocence that children come with and how that can so easily -- well, not easily, but how it can be destroyed, how it can be disturbed."

Walking into the gallery, one first sees "Health and Wholeness," twin glass pyramids that contain electric votives that provide perpetual flames while above slide projections illuminate images culled from historical archives and Johnson's family photos. AfroSolo commissioned the piece as a way to draw attention to health issues in the African American community, such as breast cancer, AIDS and hypertension.

Johnson took that theme and used her work to place it in a larger context. "We have, as a community, to decide that we're going to allow ourselves to be whole and healthy and we're going to each one of us work towards that, each one of us that can. So that's what this is about," she says.

"What I wanted to focus on and inspire us as African American, as other Africans, Africans of the Diaspora, is to take care of one another -- loving kindness, gentle words, the old lady that lives down the block or next door, taking care of her, the kids that are playing, keeping an eye on them. That is something we can do that doesn't cost a dime, that will save us, that will nourish us, and it will be a return to the ways that our grandparents and parents lived, which was very community-oriented, taking care of one another."

Some of Johnson's work, such as "The Raft of the Katrina" and her chess-piece sculpture "Empired State" express outrage at what is happening in the world, yet she remains optimistic. Her 4-year-old daughter and her friends inspire hope. "Every day with them is a new day," she says with a laugh.

Through her art and her life that also includes teaching at California State University Monterey Bay, Johnson is building a legacy for her little girl. "What I want for her is to be a kind person. I want her to be a person who pays attention to more than herself," she says. "She should be kind and loving and compassionate and caring, and give back to her communities." That philosophy illuminates Johnson's art and her prescription for healing the world. "If everybody just does a little bit, a little bit, it'll be better out here," she says. "We have so much to do and seemingly so little time."

“Stephanie Anne Johnson: Art and Theater, Legacy and Testimony”: Sargent Johnson Gallery, African American Art and Culture Complex, 762 Fulton St., San Francisco. Through Sept. 16. Noon-5 p.m. Monday through Saturday. Free.

This article appeared on page E - 1 of the San Francisco Chronicle - Aug. 24, 2006

Art is an outgrowth of her work in the theater. She had been a lighting designer for nearly two decades when she began doing slide projections of her designs. That led to learning about installation art, and from there, Johnson moved to mixed media. Most recently, she began working in stone, represented in the show by "The Gift," a sculpture in Sierra gold alabaster.

Johnson's commitment to community and to using her art for the betterment of the world is an inheritance from her parents. Her mother is a retired teacher and social worker whose work with the American Negro Theater inspired her daughter to follow in her footsteps. Her late father was a child psychologist in the Bronx, whose life was irreparably damaged by the racism of the 1940s and '50s, and who worked to combat the racism that then pervaded the schools.

"That's the kind of legacy of paying attention, of giving back, that, you know, I'm standing on his shoulders. And my mother's shoulders," Johnson says.

In the show, she pays homage to that legacy with "Perspective Box #2," combining Plexiglas, light, photographs and holographic images. "That was not an easy piece to make," Johnson says of the work that is dominated by boyhood photographs of her father. "Really, what it's about is the kind of innocence that children come with and how that can so easily -- well, not easily, but how it can be destroyed, how it can be disturbed."

Walking into the gallery, one first sees "Health and Wholeness," twin glass pyramids that contain electric votives that provide perpetual flames while above slide projections illuminate images culled from historical archives and Johnson's family photos. AfroSolo commissioned the piece as a way to draw attention to health issues in the African American community, such as breast cancer, AIDS and hypertension.

Johnson took that theme and used her work to place it in a larger context. "We have, as a community, to decide that we're going to allow ourselves to be whole and healthy and we're going to each one of us work towards that, each one of us that can. So that's what this is about," she says.

"What I wanted to focus on and inspire us as African American, as other Africans, Africans of the Diaspora, is to take care of one another -- loving kindness, gentle words, the old lady that lives down the block or next door, taking care of her, the kids that are playing, keeping an eye on them. That is something we can do that doesn't cost a dime, that will save us, that will nourish us, and it will be a return to the ways that our grandparents and parents lived, which was very community-oriented, taking care of one another."

Some of Johnson's work, such as "The Raft of the Katrina" and her chess-piece sculpture "Empired State" express outrage at what is happening in the world, yet she remains optimistic. Her 4-year-old daughter and her friends inspire hope. "Every day with them is a new day," she says with a laugh.

Through her art and her life that also includes teaching at California State University Monterey Bay, Johnson is building a legacy for her little girl. "What I want for her is to be a kind person. I want her to be a person who pays attention to more than herself," she says. "She should be kind and loving and compassionate and caring, and give back to her communities." That philosophy illuminates Johnson's art and her prescription for healing the world. "If everybody just does a little bit, a little bit, it'll be better out here," she says. "We have so much to do and seemingly so little time."

“Stephanie Anne Johnson: Art and Theater, Legacy and Testimony”: Sargent Johnson Gallery, African American Art and Culture Complex, 762 Fulton St., San Francisco. Through Sept. 16. Noon-5 p.m. Monday through Saturday. Free.

This article appeared on page E - 1 of the San Francisco Chronicle - Aug. 24, 2006